NOTES ON PLAY

Creative in Residence Juliane Foronda on archive accessibility, the privilege of nostalgia, and how board games reflect social values.

August 11, 2023 | Juliane Foronda

The annual Ontario Culture Days’ Creatives in Residence series invites artists to develop community-engaged projects to be presented during the fall Festival. This year’s lineup of residents explore themes of material culture.

Juliane Foronda is based in Toronto. Her project draws from her research at the board game archive at the Canadian Museum of History, and involves the creation of a text-based installation scattering extracted board game phrases throughout the city of Ottawa.

Before play begins, agree upon a definite hour of termination.

– Monopoly (2001) instructions (courtesy of the Canadian Museum of History archives: 2009.71.1304.1 a-b box)

My days in the archive started at 8am by getting signed in at the front desk of the Canadian Museum of History’s Collections Building. I showed photo identification and was cleared by security, scribbled my full name, arrival time, and the reason for my visit into a form, received an identification tag, and was welcomed into the restricted area by one of the Sports and Leisure Collection staff members who would be alongside me throughout my entire research period. We passed multiple doors that required special clearance until arriving in a room that had been carefully prepared for my research.

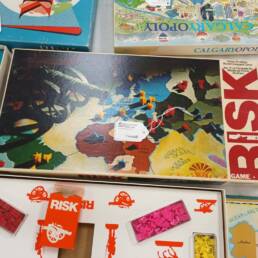

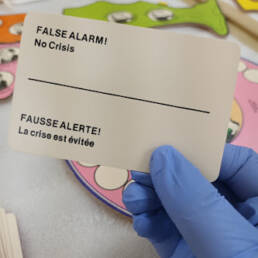

I could not help but feel the evident connection to the infamous Milton Bradley/Hasbro game Operation, given the sterile nature of archival protocol mixed with the wonder and excitement of picking through moments of past play. Donning a pair of periwinkle latex gloves, I carefully approached one of the many tables where seemingly countless board game boxes and their contents were delicately laid out for me. My senses immediately shifted from knowing these things for their familiarity, into considering them as archival objects. I wouldn’t shuffle the deck, I wouldn’t dare roll a dice. I began sifting through what felt like endless text ephemera to find just the right phrases. The gloves ensured I wouldn’t get too close – both literally and emotionally – with my left hand often shifting from gloved to gloveless between typing and rummaging through playing cards, game pieces, and instruction manuals. Time seemed arbitrary in this space.

The question is how far afield from the central core of meaning do we stray?

– Thesaurus: The Board Game (1990) instructions (courtesy of the Canadian Museum of History archives: 2009.71.658.2)

I do not enjoy playing board games. I find them to be contrived, and do not tend to enjoy the atmosphere that they produce. My investment in this research is rooted in them as artifacts, and how they reflect on society and our value systems. In French, the term for board games is jeux de société, (quite literally translating to “society games”) which, in my opinion, is a significantly more accurate term than simplifying or generalizing them to their material or structure. Some of the most celebrated board games are centred in realities of war, greed, murder, and colonization, but are packaged so perfectly in beautifully designed boxes that entice us to grab them off the shelves and play.

My work within the collection is part of my Ontario Culture Days Creatives in Residence project. It is intended to reflect on the parallels between organized games and reality through phrases from board game descriptions, instruction manuals, packaging, play cards, and the games themselves. I’m interested in how language has the power to shift our understanding, and how it can be used to control. My intention is to activate the game phrases throughout the city in reference to how board games are structured to mimic city layouts and urban planning. By pulling phrases found in the board games within the Canadian Museum of History’s Sports and Leisure archive and placing them into the streets of Ottawa, my intention is to suggest that we’re likely all pawns within the scope of society.

My time working in the Canadian Museum of History archives was so generative, and this project would not exist without the labour, generosity, and care of the entire collections team. My research was welcomed into the collections with such enthusiasm, and their knowledge and experience with this extensive collection allowed my research to flourish, especially considering my limited time with the collection. We spoke in endless tangents and anecdotes about specific games, their backstories, and our personal memories of them. These conversations led me to think heavily about the role of (institutional) archives towards social discourse. Archives and collections hold communal memories, yet are not often communally accessible, or at least not easily accessible to the general public, unless you identify as an academic or scholar. At what point does the need to preserve these memories inhibit them from truly living on?

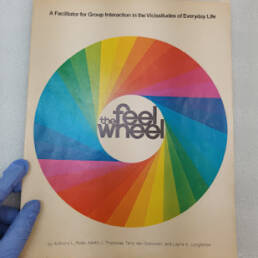

We found that emotional encounters could become an end in itself.

– The Feel Wheel (1972) instructions (courtesy of the Canadian Museum of History archives: 2009.71.1083.1 a-c)

Throughout my work in this archive, it wasn’t lost on me that board game enthusiasts were likely more deserving to experience this vast collection rather than me. Seeing household games such as Monopoly, RISK, and Clue inevitably sparked memories of my childhood, but I was also vividly aware of the intricacies of different versions or editions, or the histories of certain niche games were beyond my knowledge. To me, they were research materials: simply a means towards a larger project, and I felt unworthy being amongst what I knew were coveted artefacts to a certain community that is not my own. I could not help but wonder: do archives hold nostalgia?

I looked at one of the Monopoly boards with the same affinity as when I’d find dishware at a charity shop that we had in my childhood home. Not mine, but almost. These objects lived with us, around us, and over time have carved spaces in our memories. There’s a particular comfort that comes with time, and the privilege to feel nostalgia was not lost on me amid these boxes of potential memories.

Ontario Culture Days runs an annual Creatives in Residence program. Part of the work of the Creatives is presented during public events for our festival of free arts and culture programming across Ontario.

Find more information on Juliane Foronda’s project here, and read more about the 2023 Creatives in Residence cohort here.