Photo Credit: Ontario Culture Days

This article is the first in our series Ontario on Film written by Dave Dyment. Upcoming articles include Millbrook, Kingston and Oshawa.

By Dave Dyment

There is a market stall in Petra, Jordan called the Indiana Jones Gift Shop. It is right next to the Indiana Jones Snack Shop. Nearby is the the Indiana Jones Coffee Shop, and a second Indiana Jones Gift Shop. As far as I can tell, none of them sell any merchandise or memorabilia related to Indiana Jones. They are named this way because the third movie in the franchise was filmed nearby.

Is this merely a clever ploy to separate tourists from their money, or does this area (which houses a world wonder, incidentally) feel differently about itself because of its place in blockbuster cinema history?

In Wakita, Oklahoma there is one museum. This museum boasts a collection of Twister debris, not from an actual tornado, but props from the 1996 movie Twister. Apparently if you live in a town with only a few hundred people and a film crew comes by, you memorialize it with its own museum, even it’s a glorified corner store with some signed scripts and a Twister pinball machine.

Seeing your city on screen offers a strange sense of validation.

“Think of Florence, Paris, London, New York,” writes Scottish author Alasdair Gray, in his novel Lanark. “Nobody visiting them for the first time is a stranger, because he’s already visited them in paintings, novels, history books and films. But if a city hasn’t been used by an artist, not even the inhabitants live there imaginatively.”

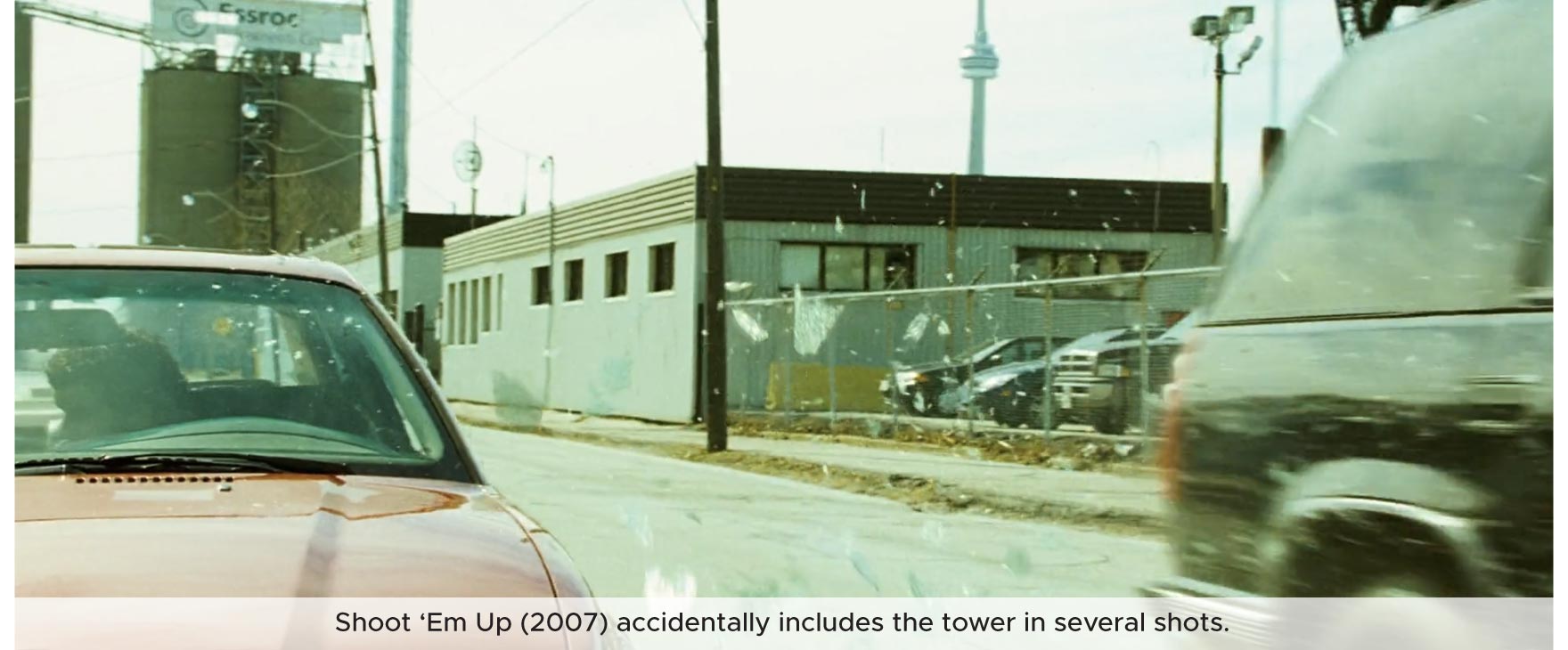

In Toronto there is a different issue to contend with: we regularly see our surroundings reflected back to us, but not our experience. Toronto is the fourth most filmed city on the planet, behind Los Angeles, New York City and London, and ahead of Vancouver, which rounds out the top five. Originally a result of a weak Canadian dollar and strong tax incentives, production now flocks to the province because of the state-of-the-art sound stages and production facilities. But Toronto is almost exclusively employed for its ability to conceal itself. The city’s own website touts “Toronto doubles for New York, Boston, Washington, Chicago and other US locales as well as international cities such as Paris, London, Morocco, Saigon and Tehran.”

New York is a film star, Toronto a stunt double.

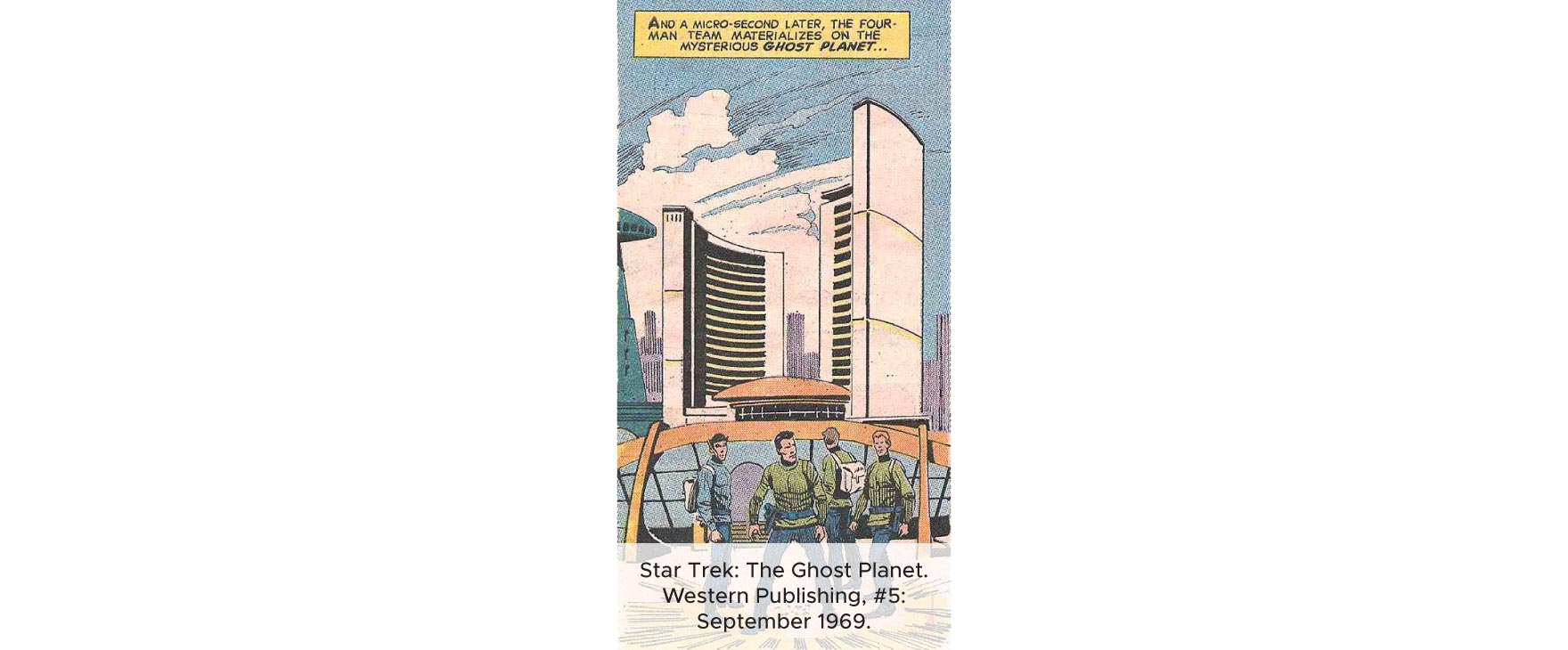

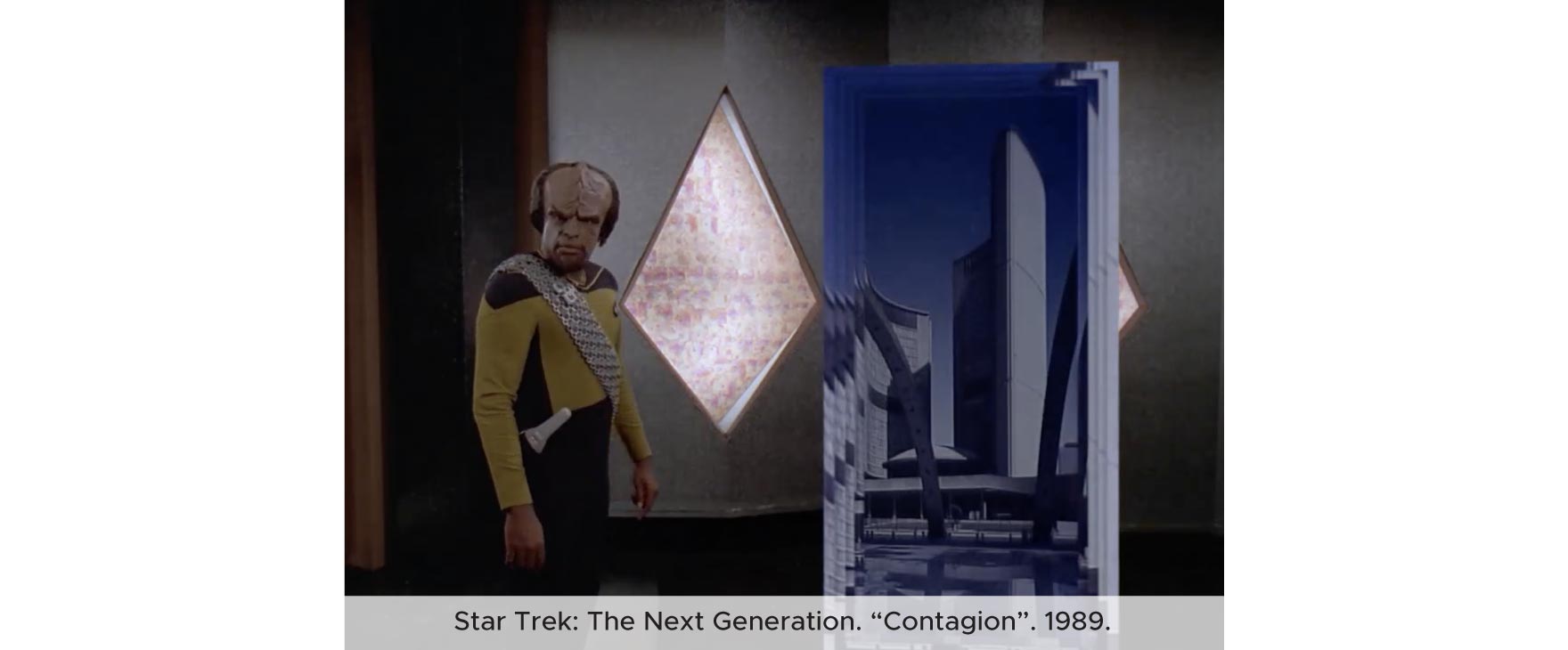

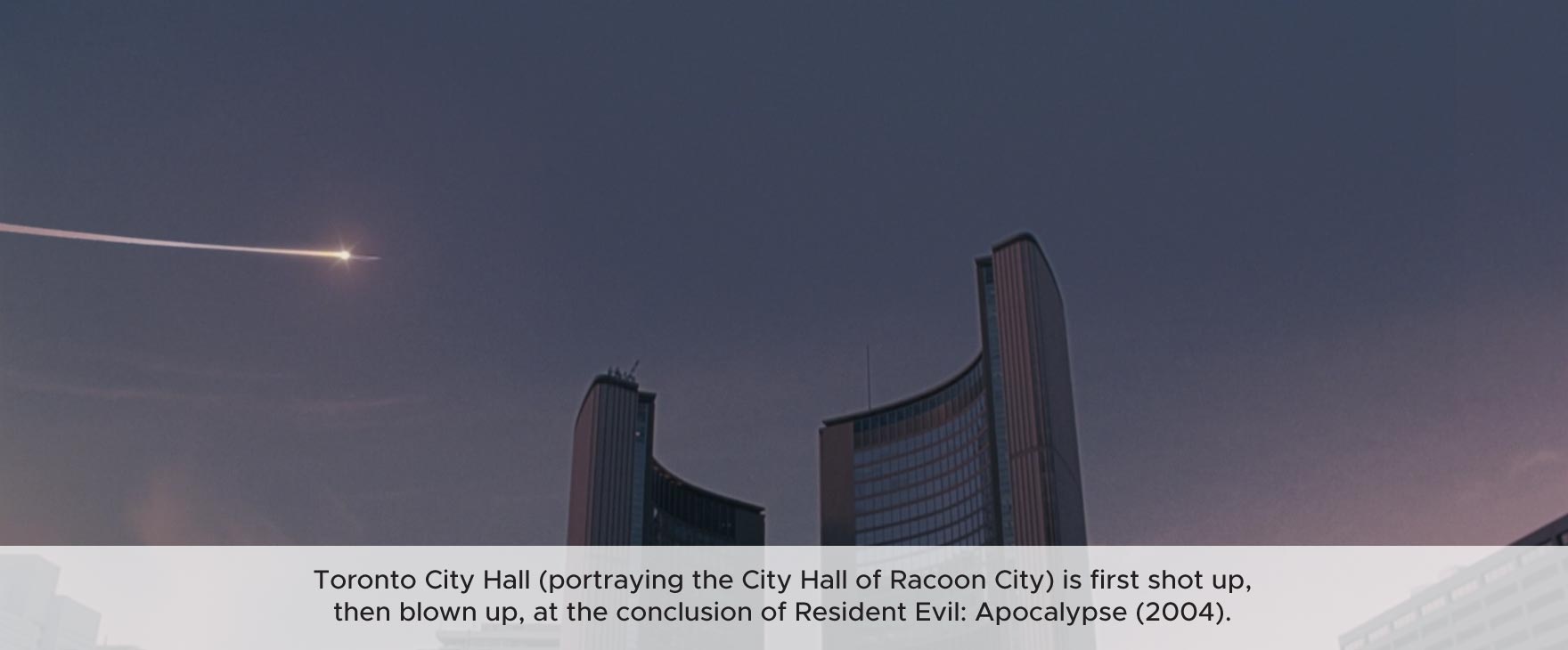

Even the city’s most distinctive buildings are easily appropriated, often used to portray corporate or military headquarters in a dystopian future. Toronto’s City Hall, with its unique twin curved towers, appeared only four years after opening in 1965 as an alien building in a Star Trek comic, and again twenty years later in Star Trek: The Next Generation. Executed enemies of the state are seen hanging from it in The Handmaid’s Tale, and the building is blown up in the 2004 film Resident Evil: Apocalypse.

Film critic Roger Ebert once joked that no matter where in Paris a scene is set, the Eiffel Tower will be visible in the background. The clock tower affectionately known as Big Ben is similarly used to indicate to viewers that the setting is London, often with a red double decker bus driving by. The Empire State Building in New York has been featured in hundreds of films, perhaps most notably in King Kong or Andy Warhol’s Empire, a static eight hour shot of the Art Deco skyscraper.

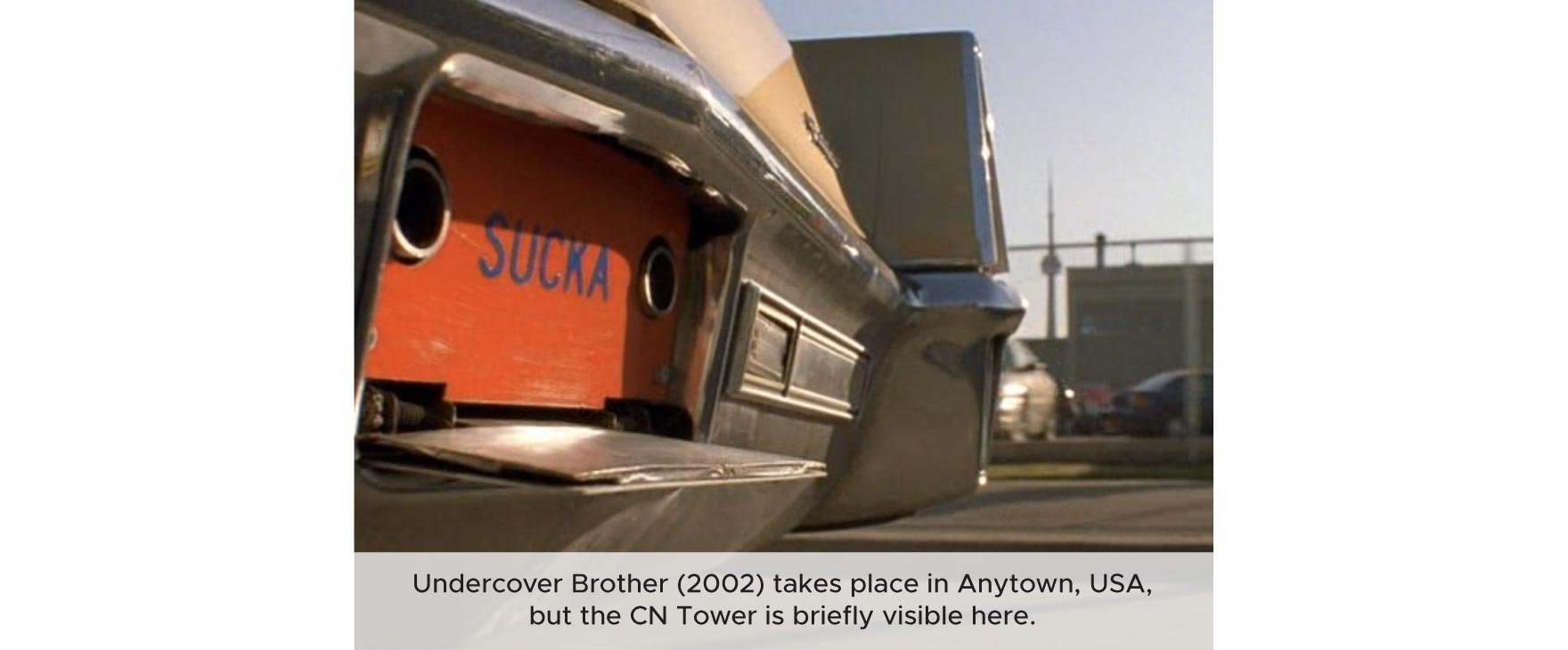

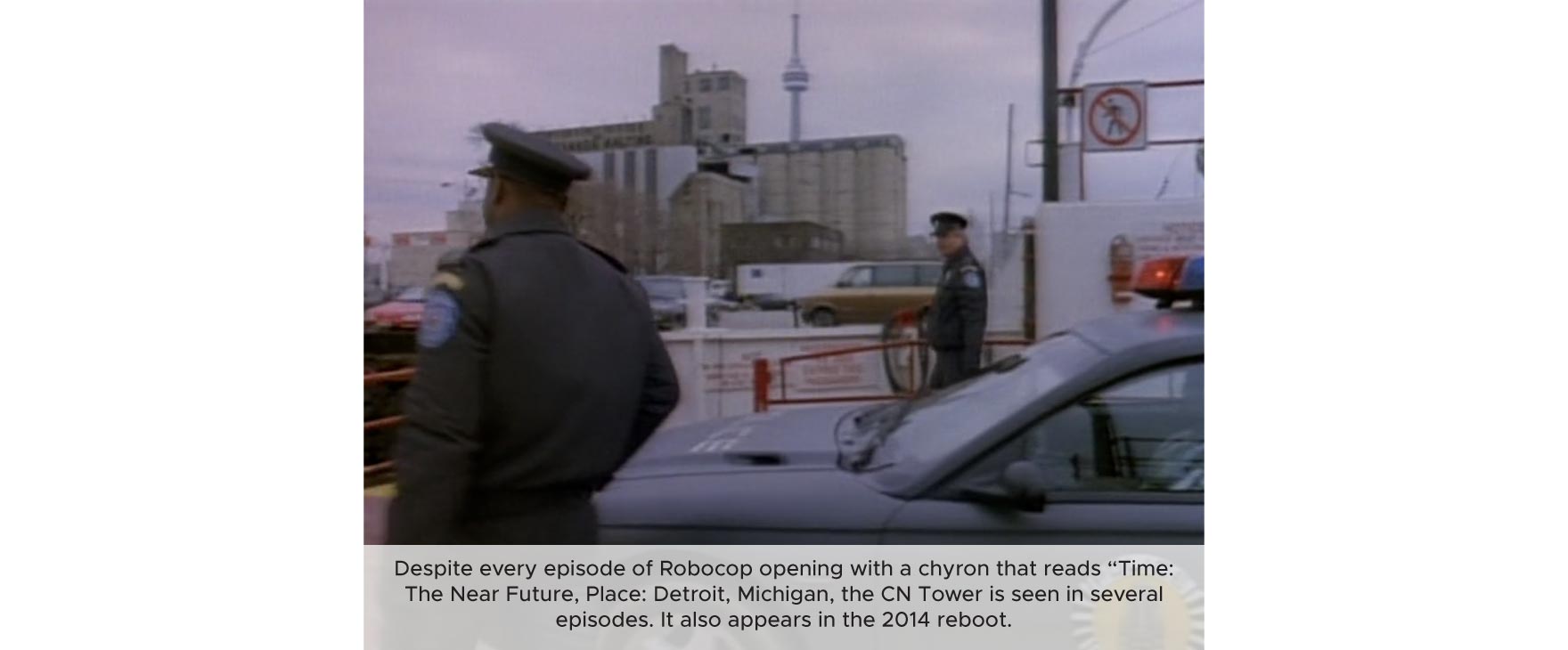

Toronto’s CN Tower is more likely to appear in a film accidentally than intentionally. Geoff Pevere opens his book Toronto On Film with a story of how Film Festival audiences literally gasped when they saw the Tower depicted in Deepa Mehta’s Bollywood/Hollywood. We are accustomed to seeing our city on celluloid, but not so nakedly.

Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale was written in Toronto and the television adaptation was filmed in Toronto, but the story takes place in the totalitarian state of Gilead, after the overthrow of the United States government. In the seventh episode, June’s husband Luke (O. T. Fagbenle) escapes to “Little America”, an area in Toronto with many refugees and fugitives from the Republic of Gilead. The crew found themselves in a unique position:

“For the first time in my career we had to add the CN Tower to the episode,” showrunner Bruce Miller told the Hollywood reporter. “Every show I’ve ever shot in Toronto you’re always pulling that out because you don’t want to let people know you’re in Toronto. Here we shot in a location where it was supposed to be visible, and it wasn’t – just from bad luck of where we had set up, and fog on the day. It wasn’t that visible so we actually had to add it in post-production, which I thought was hilarious.”

In the east end of the city is an impressive architectural achievement more likely to have been seen on screen than in person. The R.C. Harris Water Treatment Plant is a majestic sprawling complex that supplies over a third of the city’s water. Named after Roland Caldwell Harris, Toronto’s commissioner of public works from 1912 to 1945, the plant is a rare example of industrial architecture firmly rooted in the aesthetic. Dubbed “The Palace of Purification”, the plant represents the largest collection of Art Deco buildings in Toronto.

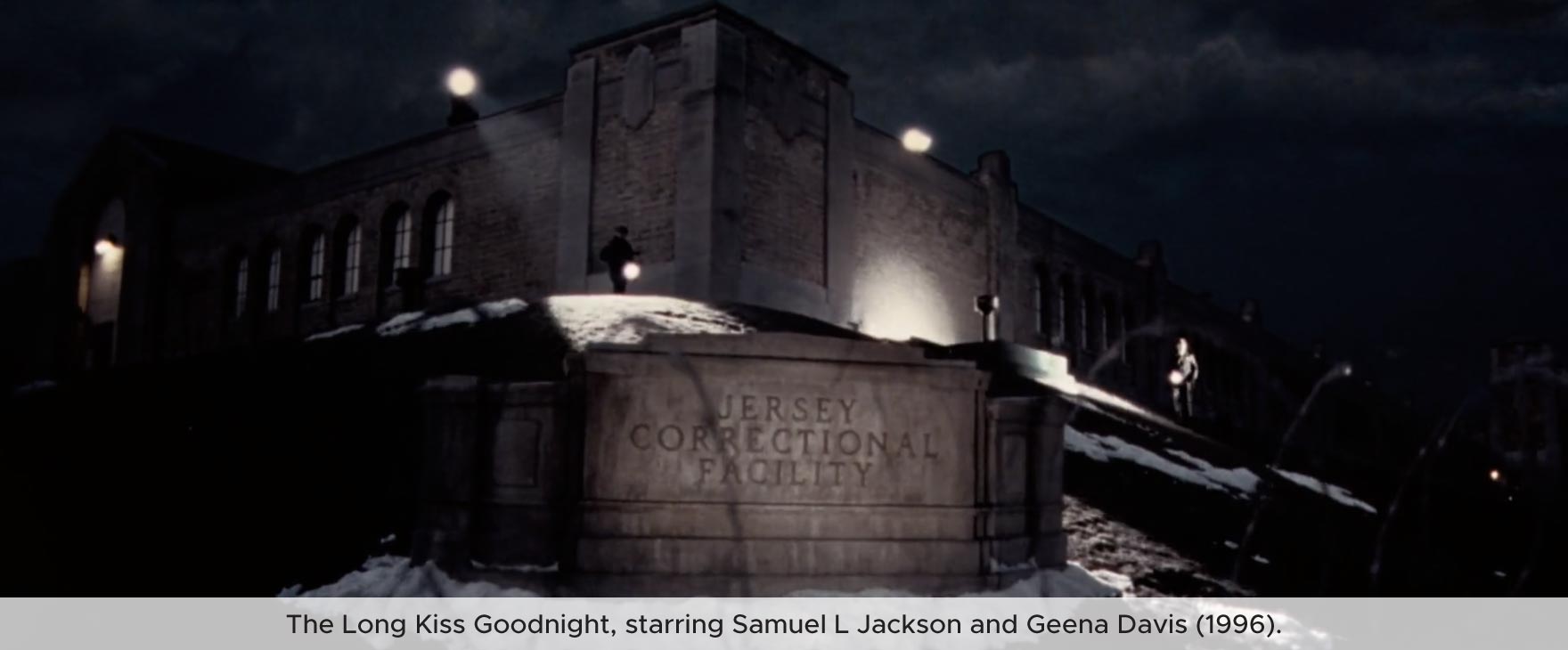

The massive compound has been used to portray a hospital (Mimic), an asylum (Robocop, In the Mouth of Madness, Strange Brew), a city on another planet (Killjoys) and – most often – a prison (The Long Kiss Goodnight, Flashpoint, Conviction, Half Baked, PSI Factor, Between, Regression, The Littlest Hobo, Due South, SCTV, etc.).

It is not only cinema and television that finds the building compelling: Michael Ondaatje writes about the origins of the plant in his acclaimed 1987 novel In The Skin of A Lion. The author describes Harris dreaming the marble walls and copper-banded roofs, and the architect imagining the space like an ideal city. “Before the real city could be seen, it had to be imagined.”

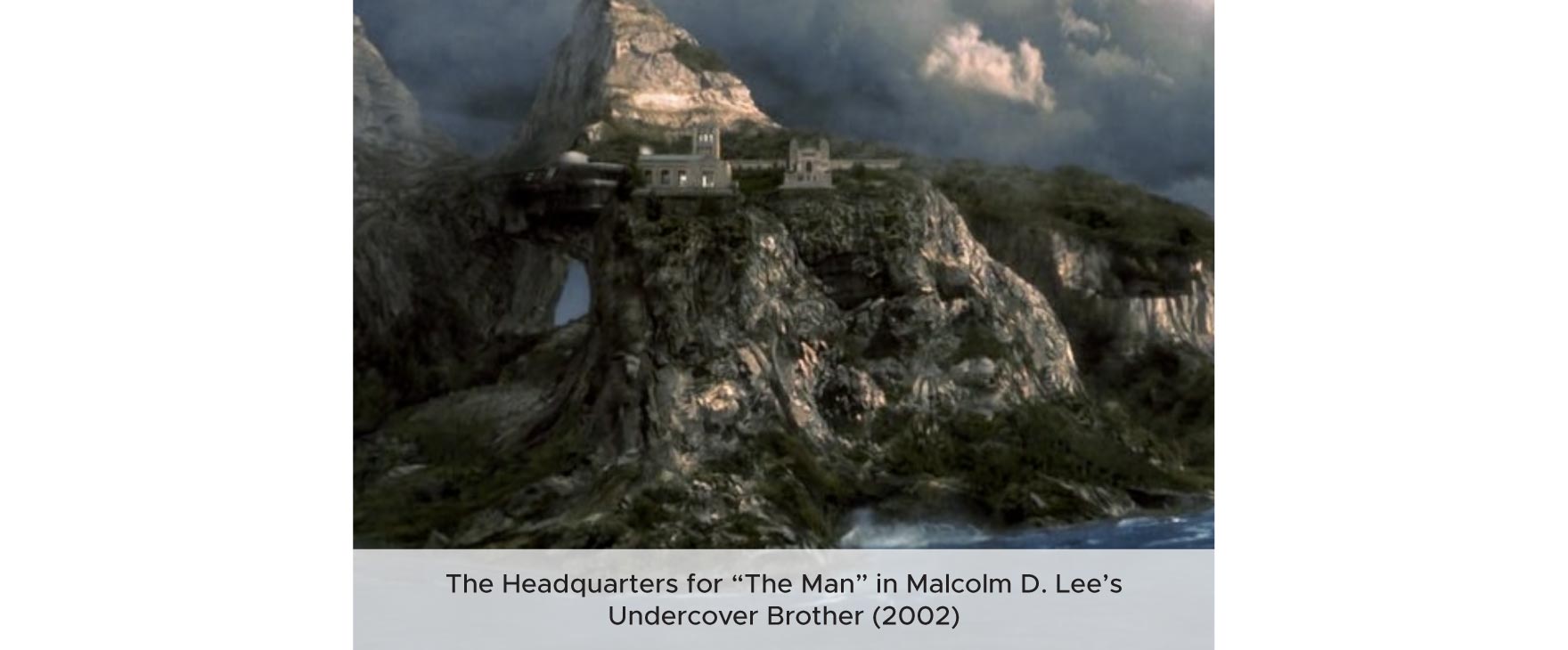

The Water Treatment Plant has also been used to portray evil corporations, often of the most generic variety. It has been repurposed as Genomex in the 2001 sci-fi series Mutant X, the sinister think-tank “The Centre” in The Pretender and – as a parody of these types of depictions – as “The Man,” in Undercover Brother. “The Man” is a secret organization that seeks to undermine African-Americans and other minorities. To create its headquarters, the RC Harris building was superimposed onto a remote island, all the better for an evil lair.

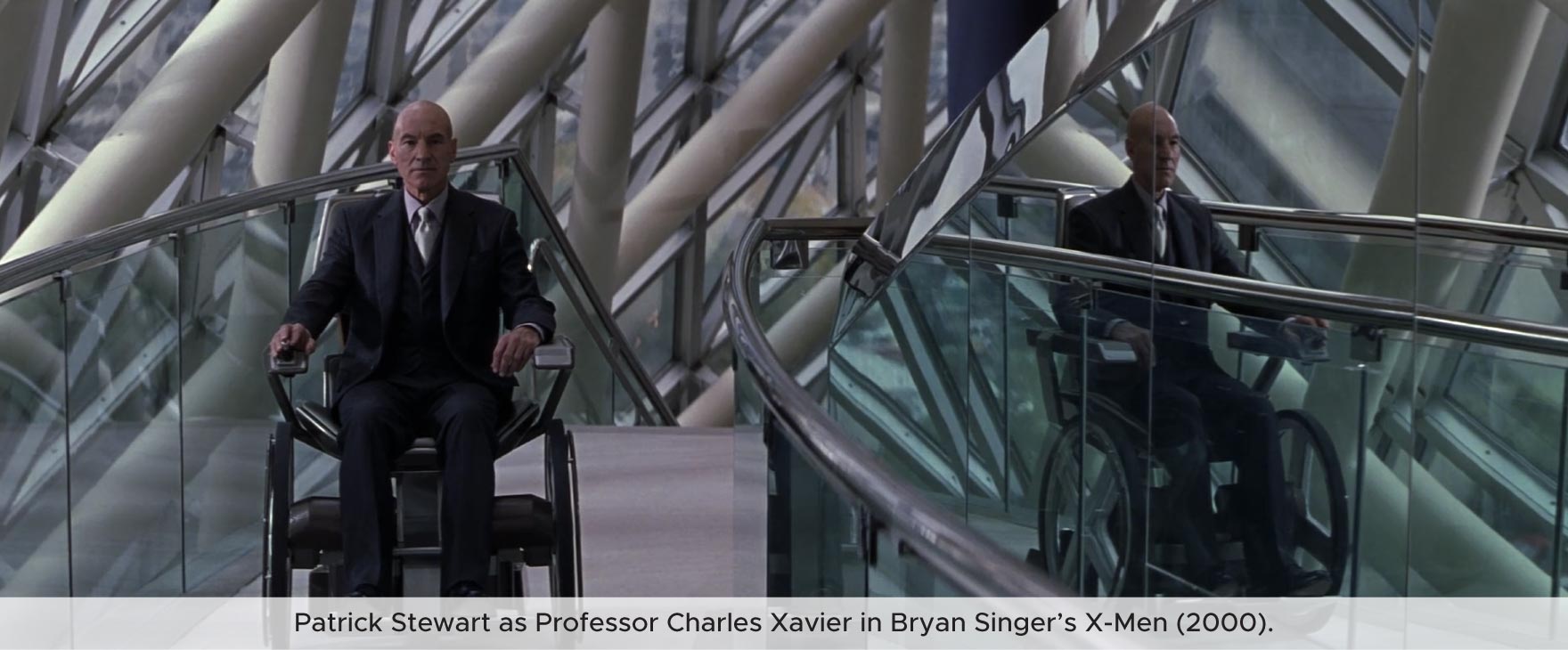

Roy Thomson Hall is no stranger to playing evil corporations (and Hannibal Lector lives just across the street). The concert hall that is home to the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and Toronto Mendelssohn Choir features a circular architectural design and exhibits a sloping and curvilinear glass exterior irresistible to sci-fi location scouts.

In addition to playing lofty sites like The U.S. Senate (X-men), The United Nations Headquarters Annex (The Expanse) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Salvation), Roy Thomson Hall has also played home to the Stoneheart Building and Vought International.

The Stoneheart Corporation – if the name wasn’t a giveaway – is an evil multi-billion dollar company in Guillermo del Toro’s FX series The Strain whose goal is to use their international power plants to trigger a nuclear winter. Vought International is the powerful corporation who owns the titular superheroes in the Amazon series The Boys.

To create Vought International tower, production designer Dave Blass took the existing window style of Roy Thomson Hall, and used it to inform the rest of the building, partly for stylistic reasons, and partly for continuity (some of the interiors are shot inside the concert hall, looking through the distinctive windows).

Hungarian professor George Gerbner coined the term ‘Symbolic annihilation’ in 1976, to describe the absence of media representation based on race, gender, sexual orientation, or socio-economic status. Is it possible that a city’s populace can feel similarly disenfranchised by their lack of representation?

Toronto is the fourth most-filmed city in the world and Chicago is sixth. But Chicago is the setting in countless iconic films and the city name appears in the title of dozens of others (even if the 2002 Oscar winning musical Chicago was shot almost entirely in Toronto). The only film with Toronto in the title is an obscure documentary called Let’s All Hate Toronto.

Arthur Erikson, the late architect who designed Roy Thomson Hall, proposed that our mutability was an asset not a liability. In “Our lack of national identity is our strength,” an article he published in the Globe and Mail in 1997, he argued that “A lack of a traditional national identity will prove to be our strength in this century as the world moves toward a humanity-wide consciousness.” By having “no history of cultural or political hegemony” we are “more open to, curious about, and perceptive of other cultures.”

A year later, in the same paper, political journalist Susan Delacourt took up the mantle in her column about national identity: “To be Canadian means to be willing to shrug off your own identity so you can imagine what it’s like to be someone else.”

Dave Dyment is an artist, writer and curator from Toronto, who recently relocated to Sackville, New Brunswick. He is currently completing a feature length film called Dead Ringer, about Toronto’s depiction in cinema. He is Co-Director of Struts Gallery, with his partner Roula Partheniou, with whom he also operates The Nothing Else Press. He is represented by MKG127 and his work can be seen at www.dave-dyment.com.

Thanks to Philip Monk, Geoff Pevere, Ruth Burns, Roula Partheniou, Meaghan Froh Metcalf, David Wellington.